EUROPEAN UNION

Legal updates: case law analysis and intelligence

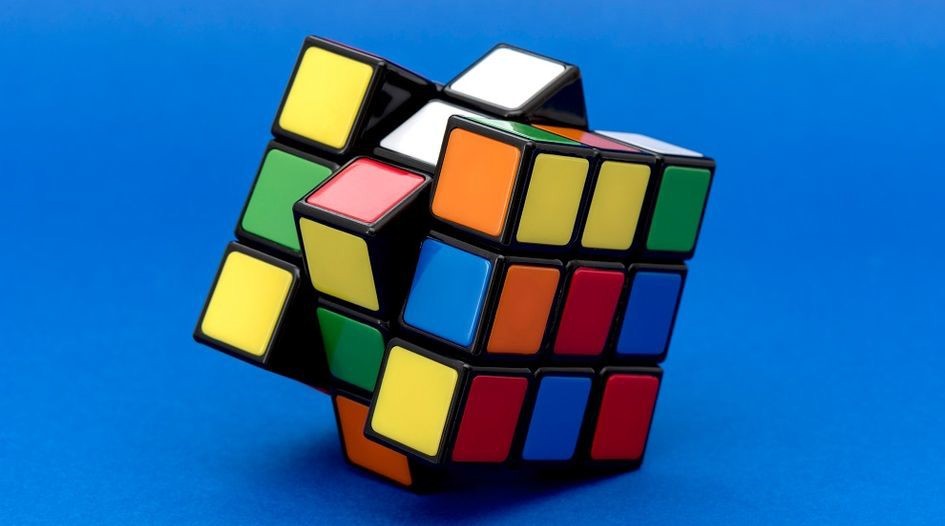

On 9 July 2025 the General Court delivered judgments in four appeals concerning three-dimensional (3D) trademarks associated with the iconic Rubik’s Cube (Cases T- 1170/23, T-1171/23, T-1172/23 and T-1173/23):

Background

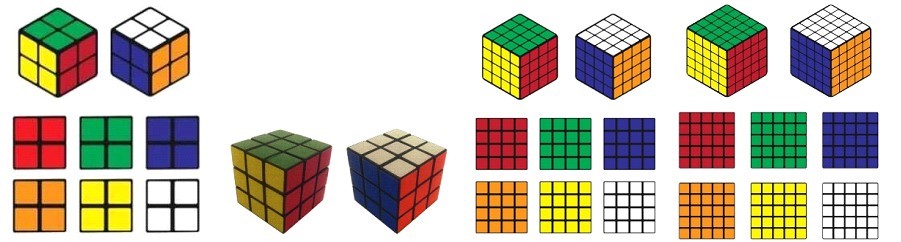

Spin Master Toys UK Ltd is the proprietor of several EU trademark registrations protecting the 3D geometric configuration of the Rubik’s Cube surfaces, which are characterised by a grid structure consisting of coloured squares. In January 2013 a Greek company, Verdes Innovations SA, filed invalidity actions against the trademarks.

The EUIPO Board of Appeal held that the coloured grid pattern of the cubes formed an essential feature of the trademarks and was integral to the shape being claimed. It concluded that the combination of six colours (red, green, blue, orange, yellow and white) on the cube’s surfaces was an essential characteristic of the marks and was necessary to obtain a specific technical result. On this basis, the board held that the trademarks should not have been registered in Class 28 as they contravened the absolute grounds for refusal under Article 7(1)(e)(ii) of Regulation 207/2009, which excludes the registration of signs consisting exclusively of the shape or another characteristic of the goods necessary to obtain a technical result.

Appeal to the General Court

Spin Master asked the court to dismiss the Board of Appeal’s decisions and order the EUIPO and Verdes Innovations to pay costs, contending that the trademarks’ essential characteristics (the combination of six colours and the arrangement of them on the cube’s surfaces) do not consist exclusively of the shape and are not necessary to obtain a technical result.

Spin Master argued that, even if the specific colours and the specific arrangement of those colours formed part of the shape of the marks, those elements are not necessary to obtain a technical result. It contended that, while it is necessary that the six sides of the cube can be differentiated, the manner in which this is accomplished is not a technical question but, rather, an aesthetic one.

The court rejected this claim, holding that, under EU trademark law, the fact that a combination of purely functional elements may produce an overall aesthetic effect does not mean that Article 7(1)(e)(ii) should not apply.

The court also rejected Spin Master’s plea that the Board of Appeal had erred in its assessment regarding “jigsaw puzzles”. Spin Master had argued that the shape of the cube does not constitute a picture and further contended that the technical result identified by the board (namely, rotating elements which have already been assembled) is not the technical result of a jigsaw puzzle, the purpose of which is to form a completed picture by fitting together individual interlocking pieces.

The court dismissed this argument and agreed with the Board of Appeal that, even if a Rubik’s Cube may not be the first example of a jigsaw puzzle which springs to mind, the term “jigsaw puzzles” must be interpreted to include 3D jigsaw puzzles. As there was nothing in the representation of the trademarks that would preclude the possibility of dismantling and reassembling the Rubik’s Cube to achieve the correct configuration, the Board of Appeal was correct in holding that the prohibition contained Article 7(1)(e)(ii) also applies to jigsaw puzzles.

Outcome and comment

The General Court dismissed all four appeals and awarded costs against Spin Master. In doing so, the court has reaffirmed that 3D trademarks are invalid if they protect a shape that exclusively performs a technical function, and this is something that manufacturers and trademark owners should be mindful of when they are designing new products or seeking to protect existing ones. Here, the grid structure and cube shape enabling rotation was held to be inherently functional, placing it outside the scope of trademark protection.